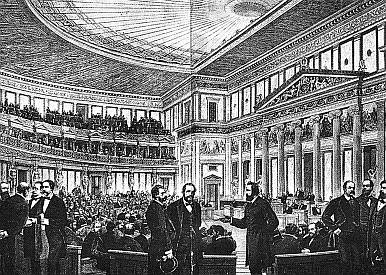

The National Assembly of the Czechoslovak Republic

A new opportunity to solve the legal question was provided by the exceptional situation after the outbreak of the First World War. The shape of the future political organisation of the newly formed Czechoslovakia had to emerge from a combinationof the intentions of the foreign resistance led by T. G. Masaryk and domestic politicians, who had renewed their activity after the reconvening of the parliament in 1917. The future parliamentary body had its roots in the thirty-eight-member National Council, a body of domestic, ethnically Czech, representation, which was reorganised in July 1918 according to so-called Švehla’s Key on the basis of the gains made by the political parties in the elections to the Imperial Council in 1911. On 28 October1918, the National Council issued the act on the establishment of the independent Czechoslovak state, in which it declared itself the executor of state sovereignty. The National Council issued the Interim Constitution, on the basis of which the National Assembly, referred to as ‘revolutionary’,met in the Thun Palace in the Lesser Town of Prague on 14 November 1918. Its composition was the result of a sixfold expansion of the National Council, with the addition of 41 deputies representing Slovakia. In total, 256 Czech and Slovak deputies sat in the National Assembly. In March 1919, this number was increased by another 14 Slovak deputies. At their first meeting, the deputies declared the Czechoslovak state a republic, deposed the Habsburgs from the Czech throne and elected Masaryk president by acclamation.

The main task of the Revolutionary National Assembly was to complete the national revolution and adopt the constitution. Representations of national minorities did not attend the Assembly. This fact may be particularly striking in view of the large German minority in the Czech lands. The absence of German deputies was caused not only by the fear of Czech politicians of the highly probable complications in the approval of the basic laws of the new state. What was important was the stance of the Germans from the Czech lands, who still in October 1918 rejected their incorporation into the new state and hoped for representation in the future Austrian parliament. A change in the standpoint of the Czech Germans occurred after international treaties laid down the new arrangement of Central Europe. However, they conditioned their participation in parliamentary proceedings on the dissolution of the National Assemblyand the calling of elections. The Czech political representation rejected this demand, referring to the ‘rights of the revolution’ (a common term in the political and legal terminology of the time) and the recognition of the Czechoslovak government in the conclusion of peace with Austria. Minorities were thus not involved in the work on the Czechoslovak constitution. The intention of the Czech representation was to call parliamentary elections only after its approval and not to risk repeating the national discord and obstruction of the time of the land diet.

The Interim Constitution gave the National Assembly wide powers. The intentions of its creators had been shaped by the experience from Cisleithania, whose political system was dominated by the executive. In the post-revolutionary period, on the other hand, it was the parliament that enjoyed a privileged position in the constitutional system.The National Assembly elected not only the president but also the government. Masaryk’s dissatisfaction with weak presidential powers resulted in an amendment to the Interim Constitution in May 1919, which granted the president the right to appoint ministers. The Interim Constitution did not limit the term of office of the Revolutionary National Assembly. It was up to the discretion of the deputies when to call the first parliamentary elections.

The draft of the new constitution was formulated by Professor J. Hoetzel; the leader of the Agrarian Party Antonín Švehla stood out in the political discussions on the final version of the text. The constitution was adopted after persistent negotiations on 29 February 1920. The Czech origin of the constitution was clear already from its Preamble, which used the term ‘Czechoslovak nation’, with which the representatives of the numerous national minoritiesc ould hardly identify. Unlike the earlier Austrian constitutions valid in the Czech lands, it proceeded from the idea of the sovereignty of the people.

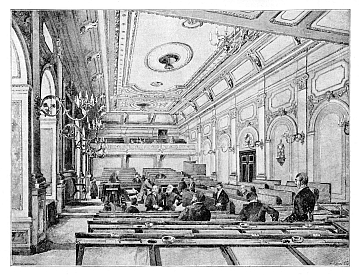

Legislative power was exercised by the bicameral National Assembly, consisting of a 300-member Chamber of Deputies and a 150-seat Senate. The method of election to the two chambers was the same; they were both elected by proportional representation on the basis of the principles of general, equal direct and secret voting rights. There were heated political discussions over the establishment of the Senate. A part of the political representation rejected the existence of a second chamber, recalling its conservative character in the days of the Austrian Imperial Council. The existence of the Senate was opposed primarily by the Social Democrats, whereas other parties wanted to differentiate the form of the Senate from the Chamber of Deputies by the method of election. In some conceptions, the second chambe rwas thus to represent the estate interests of society. Another possibility was that one-third of the senators would be elected in elections, one-third would be appointed by the President of the Republic, and the last third would be appointed by the government from representatives of public corporations. Nevertheless, a compromise establishing the Senate could only be reached if the demand of the Social Democrats that no senator be selected by any means other than election was accepted.

In the end, both chambers were elected similarly, based on a proportional electoral system. The only difference, affecting the composition of the chambers, was the age limit for active and passive right to vote. Citizens over the age of 21 could vote for the Chamber of Deputies; citizens over 30 years of age could stand as candidates. To be eligible to vote for the Senate, the citizens had to be 26 years old, and a candidate for senator had to be 45 years of age. The law set the maximum term of office to six years for the Chamber of Deputies and to eight years for the Senate. However, specific political developments erased even this distinction, and elections to both chambers were held simultaneously from 1925. These circumstances, along with its weaker role in the legislative process, led to the Senate being considered as a less significant institution in the eyes of the public. The sessions of the chambers were convened by the president, who could also dissolve both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. In order to ensure legislative activity when both chambers were dissolved, a Standing Committee was established with 24 members, of whom 16 were selected by the Chamber of Deputies and 8 by the Senate. The Standing Committee adopted measures that required the approval of the National Assembly. Nevertheless, the measures had to be accepted by both chambers after they were convened, or they ceased to be valid.

The government was accountable to the Chamber of Deputies, which could, on the proposal of 100 deputies, express no confidence in it by a simple-majority vote. For a vote of no confidence, an absolute majority of the deputies present was required. Members of both chambers had the right to interpellate members of the government. Members of the National Assembly had a wide range of immunities, which were to ensure the independence of the legislature. Deputies and senators could not be handed over for criminal or disciplinary prosecution without the consent of the chamber of which they were members. The mandate of a deputy or senator was unfettered; members of the body were not allowed to take orders from anyone and were to make decisions according to their knowledge and conscience. In political practice, however, the mandates became the property of the parties, and any loss of a mandate in the case of a breach of party discipline was decided by the election court, whose members were elected by the Chamber of Deputies. The existence of closed candidate lists also contributed to rigid party discipline. Deputies were entitled to a fixed salary of five thousand crowns per month, which corresponded to approximately five times the average salary. The two chambers met twice a year – in spring and autumn sessions. The right to introduce legislation was vested in the government or one of the chambers of the parliament. The Senate’s veto could be overridden by the Chamber of Deputies.

Political parties were a fundamental pillar of the structure of the political systém of the First Republic. Although the law did not define their activities in any way, they managed to gain a dominant position from the first years of the new state. The influence of the parties was not limited to the activities of the highest bodies; it also intervened substantially in public life at a lower level. The parties represented the national, social, confessional and interest groups of the population. A large number of parties gained representation in the parliament because the election clause was low and was not a barrier to entry to the chamber. The most successful parties in elections regularly included the Agrarian and Social Democratic Parties, with high gains of the Czechoslovak Communists being no exception either. The political scene was highly fragmented, which complicated the formation of government coalitions. This atmosphere was conducive to the creation of groupings that stabilised complicated situations. What was decisive for the functioning of the political system in the first half of the 1920s was the existence of the so-called Committee of Five (Pětka), which was an informal grouping of the representatives of the five strongest state-forming parties (Social Democratic, Agrarian, National Democratic, People’s and National Socialist). They discussed important political steps in advance, and the government and the parliament subsequently made decisions according to the agreed scenarios.

The signatures of the representatives of the Great Powers under the text of the Munich Agreement, by which Czechoslovakia lost its border territories, marked the end of the era of the First Republic. In the critical months of 1938, the parliament was not a significant and active political platform. All decisions were discussed and taken outside its walls. In the critical period between May and September, only the Chamber o fDeputies met for a short time. The Munich Agreement was not debated by the National Assembly, and the state surrendered its land without the approval of the parliament.

The tense atmosphere of the time was also reflected in the change of the constitutional relations of the state. In November 1938, the National Assembly adopted the act on the autonomy of Slovakia and Subcarpathian Rus’. At that time, the National Assembly no longer included deputies elected in the areas ceded to Germany. Czecho-Slovakia, as the new name of the state was, began to change from a democratic to an authoritarian state. The importance of the parliament was minimised by the adoption of the Enabling Act of 15 December, which gave the president and the government extensive legislative powers. At the unanimous proposal of the government, the president could issue decrees changing the wording of the constitution. The government was allowed to issue ordinances witht he force of law with the approval of the president. The parliament then recessed for the holidays and never met again. All of these measures, which were contrary to the democratic system of the separation of powers, were then justified by the exceptionality of the situation and the need to save the country.

In this spirit, even the party spectrum was to be unified, the aim of which was to suppress another of the negative phenomena that burdened the period of the First Republic – the multi-party system. The governmental right-wing entities were concentrated in the Party of National Unity, whereas the left wing United in a tolerated opposition in the National Labour Party. The short period allotted to the Second Republic was ended by the German occupation on 15 March 1939. The day before, an independent state had been proclaimed in Slovakia. In the rest of the Czech lands, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was proclaimed. The formal existence of the parliament in the political system was then definitively ended on 21 March, when it was dissolved by President Hácha.

During the Second World War, the parliament did not convene in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; the activities of political parties were naturally precluded. The only allowed grouping, within which controlled political life was to take place, was the National Partnership. The semblance of a representative body was to be formed by the Committee of the National Partnership. Considering its functions and powers, however, any comparison with a parliament is completely illusory.

In the meantime in emigration, Edvard Beneš and his associates were trying to ensure the challenged legal continuity of independent Czechoslovakia. In exile, Beneš acted as the president of a still independent state. Along with him, the provisional Czechoslovak state system was represented by the government-in-exile and the forty-member State Council, which was to perform the functions of an advisory and oversight body. The President of the Republic presented the State Council with presidential decrees for assessment – they formed the basis of normative aktivity in the extraordinary war period. The State Council, comprising representatives of various political currents, was thus, to a very limited extent, to replace the parliament.